Nature’s Corridor

James Hansen

16 September 2025

Fig. 1.2. Yellow Smoke photo from a newspaper article handed down by my father. Yellow Smoke was buried in Gallands Grove, after he was murdered in the Respectable Place saloon, Dunlap.

Predictably, soon, most young people will reject extremist views. This will be none too soon because it is the essential step leading to global political leadership that appreciates the threat posed by climate’s delayed response to human-made changes of Earth’s atmosphere. Then the annual fraud of goals for future “net zero” emissions announced at United Nations COP (Conference of Parties) meetings might be replaced by realistic climate policies. It is important, by that time, that we have better knowledge of the degree and rate at which human-made forcing of the climate system must be decreased to avoid irreversible, unacceptable consequences.

Nature’s Corridor is a concept that may help heal wounds of the past. Briefly discussed below in draft Chapter 1 of Sophie’s Planet, this concept has multiple objectives, including drawdown of atmospheric CO2. There are a lot of sub-issues raised by Nature’s Corridor, e.g., whether it makes most sense to let fires burn in the Corridor, the way they always have in nature (Silent Forests).[1] Fire fighting and “thinning” of forests, replete with bulldozers and other heavy equipment, are favored by special interests (the logging industry), but may not be the way to maximize carbon drawdown. Nevertheless, there are ways that appropriate harvesting of wood for building purposes can contribute to carbon drawdown.

Criticisms and suggestions are welcomed.

Fig. 1.1. The William Tapscott, as pictured in Mariners Museum, Newport News, Virginia.

Chapter 1. Ingvert and Karen Hansen

Ingvert Hansen, my great grandfather, was born in Ribe County in rural Denmark in 1836, as documented in The Hansen Family[2] by my oldest sister, Donna Hansen Stene. At age 19, Ingvert was converted to Latter Day Saint religion[3] by Mormon missionaries and served as a Mormon missionary himself for 4 years while working as a carpenter. In 1859 he married Karen Pietersdaughter of Holme, Denmark, and the next year they used her small inheritance to emigrate to America with a fervent hope to help in the building of Zion, the Promised Land.

Ingvert, Karen and 729 other “Saints” – converted Danish, Swiss and English Mormons – were loaded on the three decks of the Williams Tapscott, a ship built to carry freight, and set sail in May 1860 from Liverpool. The trip took 35 days in unfavorable winds and rough seas. In those 35 days, 10 passengers died, 9 marriages occurred, and 4 babies were born, one of those to Ingvert and Karen. They named their firstborn William Tapscott Bell, after the ship and its captain James Bell, which helped assure that their baby was declared an American citizen. The ship’s captain had sole authority to declare whether a child was born close enough to shore to be a citizen. The final arduous leg of their journey, by oxcart from Omaha to Utah, required 2½ months. They reached Salt Lake City in October 1860.

Ingvert carried his precious carpenter tools from Denmark to Utah. The tools aided pioneering in a forbidding Utah landscape, but Ingvert and Karen became discontented with Brigham Young’s version of the Latter Day Saint church, especially polygamy (more precisely polygyny, plural wifism). From an apostate Mormon, Alex McCord, they learned about an offshoot of the Latter Day Saint church – the Reorganized Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints, RLDS[I] – with members located mainly on the eastern banks of the Missouri River in Iowa and Missouri. So, in 1864, then with three children, Ingvert and Karen set out with their oxen on the Mormon Trail in reverse. Their goal, on the advice of McCord, was to homestake in western Iowa, which in 1864 was tallgrass prairie, with tree groves growing mainly along the streams.

Fig. 1.2. Yellow Smoke photo from a newspaper article handed down by our father. The article describes Yellow Smoke as between six feet and six feet two inches tall, weighing 200-230 pounds.

Upon reaching southwest Iowa Ingvert and Karen settled in Gallands Grove,[II] in the northwest corner of Shelby County 15 miles southwest of present-day Denison. A majority of the settlers in the Grove were Mormons, who had been persecuted and driven from their homes around Nauvoo, Illinois, but decided not to follow Brigham Young to Utah.[3] The Hansens were nearly penniless, but according to Shelby County history, Alex McCord made it known that the Hansens were “hard workers, good credit, and needed help in getting settled.”

The homestead was Eden compared to Utah, but it was hilly, rocky land, difficult to plow. Crops were lost in some years to grasshopper plague, chinch bugs, or drought and dust storms, but chickens and pigs fattened on the grasshoppers. Ingvert and Karen never strayed far from the Grove. The eighth of their 11 children was my grandfather, James Edward Hansen. Pioneer Ingvert Hansen left almost no writings. We are only aware of his diary for parts of the travel from Denmark. We know that his farming in “hardscratch” Grove soil was arduous, but he had five sons to help with the farming, and six daughters to help his wife, Karen. He retained his strong religious bent, eventually becoming the presiding Elder in the RLDS church in the Grove. Our best source of information about Ingvert’s character, my sister Donna suggests, may be the inscription on his gravestone, which reads: “An honest man’s the noblest work of God.”

One story from Ingvert and Karen’s pioneer days has been passed down through generations.

Yellows Smoke, Chief of the Omaha Native Americans, was the keeper of the Sacred Pole, the centerpiece of ceremonies, subject of sacred songs, and symbol of the tribe’s well-being. Yellow Smoke’s name came from yellow smoke stain on the pole, once displayed in the Smithsonian Museum in Washington, D.C. and now resting with the Omaha Tribe at Macy, Nebraska, according to the Crawford County History website. Yellow Smoke often visited the farms of Ingvert and his neighbor, John McIntosh. McIntosh and Ingvert probably tried to convert Yellow Smoke to the Mormon faith because Joseph Smith (founder of the Latter Day Saint church) and Brigham Young advocated that approach. In any case, Yellow Smoke expressed a desire to be buried “like a white man” in the Grove. He got his wish sooner than he would have wanted.

The most reliable account of Yellow Smoke’s demise, in my opinion, was passed from Ingvert and his oldest son to my parents’ generation. Sparsely settled western Iowa changed rapidly in the second half of the 1860s when a railroad was built across the state, reaching Council Bluffs in the fall of 1866. The town of Dunlap sprang into existence in 1867 on the Boyer River four miles west of Gallands Grove, after the town was platted by the railroad company. The second building constructed in Dunlap was a saloon named Respectable Place[4]. Chief Yellow Smoke took a liking to gambling and drinking with white men in Dunlap. According to my ancestors, Yellow Smoke demanded his winnings from a card game, the winnings being 75 cents (about $15 today). In an argument and scuffle that ensued, Yellow Smoke was struck on the head. The blow crushed his skull. Yellow Smoke managed to reach the Gallands Grove area, where the Omaha Tribe was encamped, but he died several days later and was buried in Gallands Grove.

The New York Times on 5 December 1868 reported that after Yellow Smoke was injured on the evening of 27 November “He succeeded in getting to where there were several hundred Indians encamped, about four miles east of town.” Also, “The Chief was always noted for being very friendly and strictly honorable. His band comprises some 1,500 warriors, who according to reports are gathering in fast and are greatly excited. Yellow Smoke was buried yesterday.”

According to my family, Yellow Smoke was buried on Ingvert’s property. Ingvert’s oldest son – William, born on the ship on the way to America – was 8½ years old when Yellow Smoke was murdered. William acquired most of Ingvert’s property and passed it on to his son, Billy. William related to Billy (of my father’s generation) that Yellow Smoke was buried under a tree on Ingvert’s property, and subsequently they were never allowed to plow close to the tree. An article in the 15 June 1978 Harlan Tribune says that Tribe members continued to visit the grave and camp on the sacred ground as late as 1922. That article suggests that the grave may have been on the McIntosh property, but I believe that the information passed from William to Billy is more credible than a newspaper article discussing what it describes as a “legend.”

Gallands Grove and surrounding areas changed rapidly within one generation of settlers. We have no writings by Ingvert or his wife Karen describing their Iowa homestead. However, the Grove sits near the adjoining corners of four counties: Crawford, Shelby, Harrison and Monona. Harrison County historical records[4] include anecdotes and reminisces of early pioneers that are revealing about the land and its people. One article, titled “Indian Troubles,” describes an event 17 years after Yellow Smoke’s death:

“The last difficulty with Indians in this part of the country was in 1885, when a band of about three hundred were in the habit of crossing the Missouri river into Harrison County. They were quite friendly, but annoyed the citizens very much by pilfering stock and poultry. To put a stop to this the whites, twenty in number, assembled and met the band when they had crossed the river. The twenty whites captured the three hundred Indians, loaded their bows and arrows into wagons and took them over the county line at Honey Creek, Pottawattamie County. The Indians were half starved, and the humane white people gathered together and raised a fund with which a steer was bought and given to the Indians, who seemed to greatly appreciate the act of kindness. After the feast, the day following, they went over the river to their homes in eastern Nebraska.”

Humanity of the settlers is a matter of perspective. As white settlers moved in, Native Americans – including the Sioux in northwest Iowa and the Omaha in southwest Iowa – were pushed further west. The federal government repeatedly signed and violated treaties with Plains tribal leaders. The Sioux were granted a 60-million-acre Great Sioux Reservation by the Treaty of Fort Laramie in 1868, but government interest in resources on the land resulted in continual shrinkage of the area, to 12.7 million acres by 1887.[5] The last resistance of plains tribes was marked by the Wounded Knee[6] massacre of 1890, which the Bureau of Indian Affairs portrayed as a battle.[5] The Bureau feared the Ghost Dance, a ritual of a quasi-religion that revived in the late 1880s. Not entirely unlike the origins of the Mormon faith, a Plains leader of the Paiute tribe, Wovoka, had a prophetic dream he interpreted as instructions from God: they should remain peaceful, but perform a ritual circle dance. If they danced enough, God would return Earth to its natural state that existed prior to arrival of European colonists. As the ghost dance grew in popularity among the Sioux, a frightened Bureau asked Washington for more military support, culminating in the confiscation of weapons by the U.S. Cavalry at Wounded Knee on 28 December 1890. When a scuffle broke out, cavalry members on a hill overlooking the encampment opened fire with Hotchkiss (machine) guns. The U.S. Army buried 146 of the Native Americans in a mass grave on the hill. Almost half of the estimated total 250-300 deaths were women and children.

Forced assimilation of Native Americans had a side effect on the land. For millennia, Native Americans had a nomadic lifestyle, hunting for game; but there was little game in small, semi-arid reservations on which they were consigned. The government encouraged them to farm and raise livestock, but the reservations were ill-suited for that. The land was altered mainly by white settlers, as described by pioneers Sally Young and D.W. Butts.[4] Young wrote: “We located in this county in 1850 and found, as we thought, the garden of Eden, a vast prairie of beautiful flowers and a great abundance of wild fruits. At this time the country was very thinly settled, our nearest neighbors being six miles away.” She complained about flies and mosquitoes, but continued “There were oceans of game, tons of fall acids in the shape of plums and grapes. The thousands of deer which roamed up and down the valley…were to be had at the little cost of shooting and dressing, and gave to the larder all, yea, perhaps, better than is now experienced by many, who at present live in this, what is termed the land of plenty. Great droves of wild turkeys lined the skirts of the interior timber track, and honey was far more plentiful then than now.”

Butts decried loss of the deep-rooted 6-foot prairie grass that, except for occasional tree groves, once covered western Iowa, noting that prairie grass was succeeded by 2-foot “tame grass”: “The grass, the natural product of this valley, was so high and luxuriant for miles and miles that horsemen might hide from each other at a distance of two hundred yards. Quite as surprising as this true statement is the rapid change by which this tall grass disappeared very quickly after the white man appeared with cattle and crowded out the deer and the elk and the red men. We expected to see the range gradually reduced, but were hardly prepared to see it go down from six feet to two feet in a few years. However, the wild hay of this section has been a mine of wealth to many, and it is yet to those who had the foresight to save it from the flock and plow. Forty years ago, this part of the state was noted for grass and hay, as it is now for corn and hogs!”

Modern agriculture feeds a large population, but with flaws that affect human health and the environment. Native Americans and tallgrass prairie have much to teach us about living with nature. The knowledge can help improve agricultural practices, restore biological diversity, increase soil productivity, and restore carbon to the soil, changes that will help limit human-made climate change. Perhaps we can find a way to do this that helps heal the wounds of past injustice. First, let us recall the deep history of Yellow Smoke’s ancestors, the first Americans.

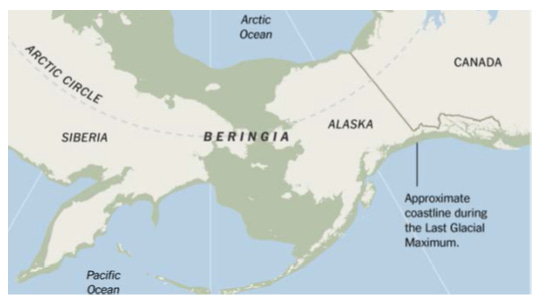

Fig. 1.3. Beringia land extent included the green area during the ice age.

Earliest archeological evidence of humans (homo sapiens) is in Africa about 300,000 years ago. Humans spread into Asia at least 60,000-80,000 years ago,[7] but the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans almost isolated the Americas, which may have remained free of humans until the ice age that preceded the current interglacial period, the Holocene. During the ice age, which peaked about 20,000 years ago, a large ice sheet covered most of Canada and northern parts of the United States, including the locations of Seattle, Minneapolis and New York City. So much water was locked in ice sheets that sea level was about 125 meters (400 feet) lower than today.

Lower sea level exposed the continental shelf around Alaska, creating a vast land area – dubbed “Beringia” – encompassing a land bridge between Asia and North America (Fig. 1.3). Humans from Siberia, who were adapted to living in cold climates, moved into Beringia. The land had shrub vegetation, trees, and large animals, which provided the Beringians with fuel and food. Archeology and genetics imply that Beringians were isolated for several thousand years, but, as ice melted, they moved freely. These Native Americans, the founding people of North, Central and South America,[8] occupied the Americas throughout the Holocene, the past 11,700 years.[III]

When Columbus arrived, half a millennium ago, there were about 10 million Native Americans in what is now the United States, and 50 million throughout the Americas, with these populations uncertain by about a factor of two. Immigrants from Europe – via diseases they brought and warfare – wiped out more than 90 percent of the Native Americans. Efforts to force assimilation into white society were long pursued.[9] Mistreatment of Native Americans is now historical fact. We tend to briefly note the uncomfortable facts in our textbooks, and then put them out of mind, perhaps believing that we cannot change history – but tomorrow’s history is being written today.

Nature’s Corridor is a dream, a concept of contiguous land stretching north-south from the Arctic through North, Central and South America, land that allows free migration of wildlife. This corridor would permit substantial restoration of natural conditions. E.O. Wilson proposed[10] that half of Earth’s land be designated a human-free reserve to preserve biodiversity. Much of Wilson’s objective could be achieved with a region in the American West that grows over time, encompassing existing reserves and national parks – eventually forming Nature’s Corridor.

Climate change and other human-imposed stresses on nature create an urgent need to find a plan for species preservation. Climate change also draws attention to the need to reduce atmospheric carbon. Native Americans could help devise and implement a plan to restore part of our land to its natural richness, including tallgrass prairie and forests that provide habitat for wildlife and draw down atmospheric carbon dioxide. Nature’s corridor could be open to all for respectful recreation, an escape from our high-paced, turbulent world.

For the next chapters of this book, I wanted to describe my parent’s struggle to make a living as itinerant farmers. As the fifth of seven children, I was four years old when they reluctantly gave up on farming and moved to town. I can barely remember the last farm, but my four older sisters have vivid memories. I dug into the 390 page The Hansen Family[2] written by my sister, Donna, and her husband, as well as 62 pages of unpublished vignettes[11] on our childhood written by another sister, Eleanor Hansen Maiefski, who was our story-teller in the time when we had an exuberant child-filled bedroom. These information sources raised questions, which led to hundreds of email exchanges with all of my siblings.

As I learned more about my parent’s life, it seemed that they had inherited a situation with odds stacked against them. Something strange must have happened during my grandparent’s generation, the generation that followed our pioneer great grandparents, Ingvert and Karen.

[I] The RLDS church changed its name to Community of Christ in 2001. It reports about 250,000 members today.

[II] Abraham Galland was the first white settler in Shelby County, building a log cabin in Gallands Grove in 1847.

[III] The land bridge between Asia and North America existed throughout the 100,000 years prior to the Holocene. Archeological evidence suggests that some migration into the Americas may have occurred prior to the main late ice age wave from Beringia.

[1] Hansen J Silent Forests, CSAS Communication, 11 June 2021

[2] Stene CS, Hansen Stene D. The Hansen Family, 389 pp, Library of Congress CCN:2009902650, 2009

[3] The LDS movement arose in an early 19th century period of Protestant religious revival, which some scholars relate to rejection of the rationalism of the Enlightenment. Science and reason alone do not satisfy the need of people for a spirituality that provides strength and gives meaning to their lives. Joseph Smith founded the LDS movement in western New York after having visions in which he claimed God instructed him not to join any existing church. He said that an angel showed him the location of golden plates with writing that he translated, with divine assistance, to a new sacred text, the Book of Mormon, which he published in 1830 as a complement to the Bible. As Smith’s following grew, local opposition forced repeated moves of the group, eventually to a small town in Illinois that they named Nauvoo. Nauvoo’s population reached a peak of about 14,000 rivaling that of Chicago, but renewed tensions with non-Mormons resulted in the murder of Joseph Smith by a mob in 1844. Most Mormons accepted Brigham Young as the new prophet and leader and emigrated with him to the Utah Territory. Under Young, the LDS Church openly practiced polygyny, which Smith had instituted in Nauvoo. The LDS Church officially ended plural marriage in 1890, and today members who practice it are excommunicated. The LDS Church extended its reach via a vigorous international missionary program, growing to a membership of about 15 million.

[5] Hudson M. Wounded Knee Massacre, United States history, Encyclopedia Britannica, last access 29 July 2023

[6] Brown D. Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee, Holt, Rinehart & Winston, 487 pp, 1970

[7] Soares P, Ermini L, Thomson N et al. Correcting for purifying selection: an improved human mitochondrial molecular clock. Amer J Human Genetics, doi:10.1016/j.ajhg.2009.05.001, 2009

[8] Rutherford A. A Brief History of Everyone Who Ever Lived, Orion, 2016

[9] Fonseca F. US finds 500 Native American boarding school deaths so far, 11 May 2022

[10] Wilson EO. Half-Earth: Our Planet’s Fight for Life, Liveright Publ Corp, 272 pp, 2016

[11] Surviving After the Great Depression, Eleanor Hansen Maiefski, 62 pages, unpublished

Thoughtful, well-written essay and the personal history is fascinating. However, I distressingly believe whether it's nuclear or renewables, neither can succeed. Both are dependent on fossil fuels to realize, and the opinion of oil geologist Art Berman is that we have just a handful of decades before harvesting it fails from plummeting EROI. We can already see that in Big Oil's turn to tar sand and shale oil since the early 2000s, far less lucrative projects as evidence.

We are headed for a low energy world, and the truth isn't being told. The Arctic is becoming an irreversible GHG emitter, and the Greenland ice sheet is fated to melt completely. That was locked in by the late '50s when we exceeded 300ppm of CO2. Evidence points to the formation of the ice sheet around that number which of course is far exceeded now.

Boreal forests are burning up, and the rainforests may be tipped. The oceans have absorbed about all the heat they can.

I'm not seeing a way out. I would love to be convinced there is still a path.

Thanks for this Dr. Hansen. However, I’m curious what evidence supports your assertion that “Predictably, soon, most young people will reject extremist views.”